“An Interesting Answer to The Interesting Narrative”

Michael J. Becker and Devin Leigh expand on the origin of their piece in the October 2025 issue of the William and Mary Quarterly.

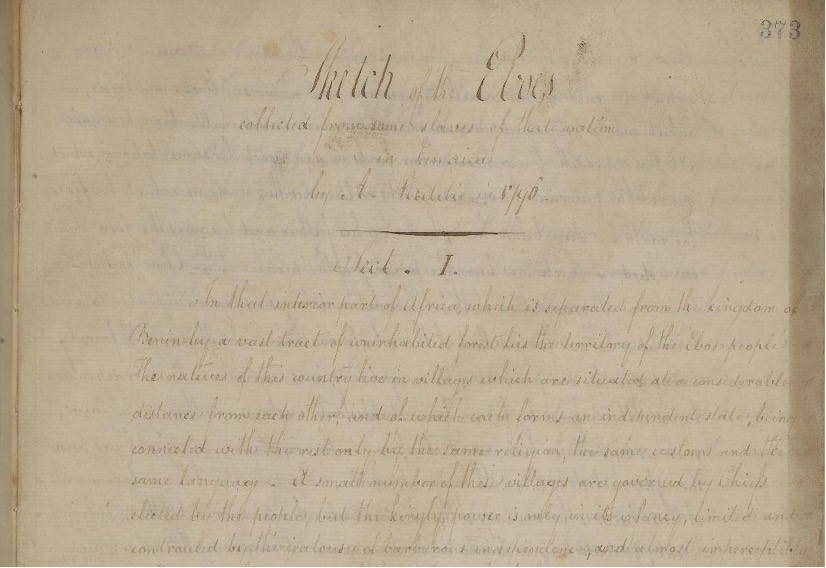

The first page of Andrew Reddie’s “Sketch of the Eboes” from 1796. © The British Library, London

As the first memoir written by a formerly enslaved person, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, the African is a text well-known to early Americanists. Published in London in 1789, amidst a nationwide campaign to abolish the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the book was an immediate success. It went through nine editions in less than a decade, inspired unauthorized versions in the US and multiple European countries, and prompted Equiano to travel the British Isles on a widely publicized speaking tour.

But what about the Caribbean? In Equiano’s day, the British empire’s sugar colonies were both economic engines and bastions of slavery. Enslavers and colonists there were certainly following the abolitionist debates and weighing in on publications by other leading advocates. But despite Equiano’s fame in Britain, scholars have little sense of their reaction to his intervention. Now, in an article in the October 2025 issue of the William and Mary Quarterly, we present what might be the best evidence to date of The Interesting Narrative’s reception by the Caribbean planter class.

The article in question, “Answering Equiano: An Enslaver’s Sketch of Igboland in an Age of Abolition,” is the result of a nearly three-year collaboration between us. It was done mostly over Zoom, as we are based at universities on opposite ends of the United States, one at the University of Maryland College Park and the other at UC Berkeley. It unfolded as follows.

The project began in the summer of 2022, when Michael was conducting research at the British Library. While searching for something else in the catalogue, he saw a stray manuscript about Jamaica filed in an unexpected place – bound with papers belonging to Sir Stamford Raffles, a British colonial official in what’s now Indonesia. Dated to 1796, written by someone named “A. Reddie,” and titled “Sketch of the Eboes collected from some slaves of that nation in Jamaica,” the text was an ethnography of enslaved people from Igboland, a region of southeastern Nigeria, based on interviews the author claimed to have conducted in Britain’s most profitable colony.

Several months later, Michael emailed Devin to get his perspective on the source. (We had first met while conducting research in Jamaica about five years earlier.) Michael thought that, given Devin’s interest in early modern ethnographies of Africa, he might help contextualize the sketch. Initially, Michael proposed they transcribe and annotate Reddie’s sketch and submit their edition to the WMQ’s “Sources and Interpretations” series.

In our early research, we uncovered the identity of the text’s author and the basic outline of his life. We learned that “A. Reddie” was “Andrew Reddie,” a Scottish migrant who lived in Hanover Parish, northwest Jamaica, between 1791 and his death in 1820. Educated at Edinburgh High School and the University of Edinburgh, he sought his fortune in Jamaica after being laid off as a clerk in the city’s customs house. Likely starting out as an overseer or bookkeeper on other colonists’ estates, he soon became comptroller of the customs at Lucea, Hanover’s port, as well as a landowner and lawyer. Eventually, he married a mixed-race woman named Elizabeth Baldie, with whom he had seven children.

Despite being previously unknown, Reddie’s sketch appeared at first glance to be a fairly conventional proslavery text, one that represented enslaved peoples as endemically savage in an attempt to counter anti-slavery narratives accompanying the rise of Britain’s abolition movement. Since at least the publication of Philip Curtin’s The Image of Africa in 1964, scholars have noted the politicization of Africa in the context of Britain’s late-eighteenth century slave-trade debates. This text seemed like it might be little more than another example of that.

And yet, as we discussed the source, we realized what made Reddie’s work stand out was its specific focus on Igboland. Igboland was not originally a site of Great Britain’s trans-Atlantic slave trade but became one only in the decades following 1730. As such, the region was generally ignored by European writers on West Africa until 1789, when Equiano claimed to have been born there in his memoir. Many Britons had written about Igbo people in the diaspora. However, as far as we could tell, Reddie’s sketch was only the second-earliest detailed description of the Igbo and Igboland in the English language.

From here, we began to explore the idea that Reddie intended his “Sketch of the Eboes,” at least in part, as a proslavery response to Equiano’s memoir. We knew that Reddie had previously printed poetry in Edinburgh Magazine and had laid out the sketch in a publication-ready format. We knew he had been a university student in Edinburgh when Equiano’s memoir was published to great acclaim and advertised in the city’s prominent Scots Magazine. We also knew he had family living in Edinburgh when Equiano toured that city and issued an Edinburgh edition of The Interesting Narrative in 1792. Perhaps they or someone else had asked Reddie to look into its representation of Igboland after he arrived in Jamaica.

Although Reddie’s sketch doesn’t mention Equiano or The Interesting Narrative, this is not proof the book wasn’t on his mind. In fact, it is consistent with how enslavers treated many Black would-be interlocutors, from poet Phillis Wheatley to writer and shopkeeper Ignatius Sancho. Believing Black people did not belong in “civilized” conversations about science, industry, or the arts, and perhaps fearing that acknowledging their writings would legitimize them in debates over slavery, enslavers generally ignored them. Having studied the published and unpublished papers of enslavers for his dissertation, Devin had not found a single mention of Equiano or his memoir beyond a few previously known pseudonymous newspaper articles.

These silences were especially loud in the Caribbean. Although British Caribbean enslavers were known to have imported the most popular texts of the day, there is apparently no positive proof as of yet that Equiano’s memoir was among them. Contemporary library records have not survived, forcing scholars to look for book titles in less comprehensive sources, such as colonists’ estate inventories and lists of imported books printed in local newspapers.

Internal evidence also supports our theory that Reddie wrote his “Sketch of the Eboes” with The Interesting Narrative in mind. Beyond the fact that his sketch discusses the same subjects as the first chapter of Equiano’s book – itself an ethnographic overview of Igboland – there are two particularly notable passages. One closely mirrors Equiano’s description of his kidnapping and the other rejects his claim that Igboland was associated with the Kingdom of Benin.

In a feature-length article in the October 2025 issue of the WMQ, we set out our argument in greater detail. Reddie’s sketch, we contend, is partly a response to Equiano’s autobiography. It suggests that Caribbean enslavers were not just aware of Equiano’s memoir, but that they tried to respond to its portrayal of Igboland. More broadly, and taken together, we also argue that these two texts are the product of a broader “Igbo moment” in the early-modern Atlantic World.