Michael A. McDonnell, University of Sydney

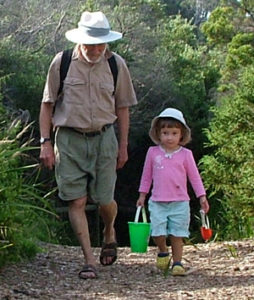

Rhys on a walkabout with his young friend Carys McDonnell. Photo courtesy Michael A. McDonnell

Inevitably this will be personal. Rhys was much more than just a fellow scholar of Virginia and the Revolution. He was a welcoming colleague, a mentor, a cheerleader, an anchor, a grandfather to my children, and a dear friend. Anyone fortunate enough to have met Rhys will appreciate that he could be all this, and much more. We already miss him, desperately.

I cannot begin to make sense of all he was. Elsewhere, I have written and spoken of his scholarly achievements. Others have written much, are writing more, and will yet pen celebratory and critical analyses of Rhys’ work. This is a personal reminiscence. For this, I make no apology. I am sure Rhys would agree that it is only in personal relationships that we can see someone’s real measure. My engagement with Rhys’ work first made it clear that he was an exceptional and gifted historian. But my friendship with Rhys made it clearer why. At every turn he inspired, he energized, he empathized, he listened, and he told stories—qualities that made Rhys a great scholar, but also, and much more importantly, a great friend to us all.

Rhys and I first crossed paths in the U.K. We both found our roots in the Celtic world and the migratory currents of the Commonwealth. I was born in Wales and left at the age of five for Canada. Rhys’s father was born in Wales, too, and his mother in Scotland. They met in South Africa, where Rhys was born in 1937. In 1959 Rhys returned to the U.K. when he won a Rhodes Scholarship and began his career reading modern European history at Balliol College, Oxford. Just over thirty years later, in the same College library where Rhys had labored years before, I was galvanized by one of the first essays of his that I read—“Dramatizing the Ideology of Revolution: Popular Mobilization in Virginia, 1774–1776,” published in the pages of the bicentennial issue of the William and Mary Quarterly in July 1976—a preparatory study, if you will, for the Pulitzer Prize-winning book to come.

I was struggling to come up with a topic, and Rhys’s essay took me far into exciting realms beyond the sometimes sterileworld of quantitative history. It was here that Rhys began his exploration of the symbolic worlds of ordinary people; examining what he called the oral-dramaturgical processes that dominated the lives of a largely preliterate society. Rhys made an exciting and breathtaking clarion call, reinvigorating the topic of Virginia as a subject of serious study. Few people have made Virginia’s colonial and revolutionary history comealive as he did.

But if Rhys’ revealing work helped inspire me to rethink the world of Revolutionary Virginia, to challenge that monolithic picture historians had drawn, he also provided me with the tools necessary for that project. In “Dramatizing the Ideology of Revolution,” Rhys not only took up the cause of those of us who insisted on writing the history of those we often arrogantly called the “inarticulate,” but he also gave us the means of doing so, a critically important development for the source-impoverished world of Virginia.

In effect Rhys expanded our understanding of politics in the Old Dominion. In his hands, the pluck of the banjo was imbued with as much social and political meaning as a vote at an election. You don’t have to agree with Rhys’ conclusions to appreciate the fact that he forced us to rethink the sometimes revolutionary meaning of ordinary, commonplace events. Though he did not invent the study of political culture, his study reinvigorated Virginia historians with a sense of the possible. He gave us a glimpse of a multi-layered, multidimensional Virginia that few of us guessed was there. Rhys took us to the heart of face-to-face communications in Virginia—never again will we—or at least should we—take for granted, or as a given, relations between man and woman, black and white, farmer and planter, poor and rich.

I was not, of course, the first or the last scholar to be inspired and energized by Rhys’s work. His first book has been variously described as a landmark of cultural history and the book most responsible for reinvigorating discussion of eighteenth-century American society both within and without Virginia—within Virginia because of its compelling and provocative account of political and cultural change in that place; without Virginia because Rhys pioneered a pathbreaking ethnographic methodology that ensured its influence would extend beyond the borders of the Old Dominion into many and varied fields of early and more contemporary American history. Without Virginia, too, because of the book’s impact and influence on diverse fields outside of American history. many colleagues in the disciplines of anthropology, social psychology, law, politics, and religion, to name but a few, have been inspired by his study.

Still, it was only when I crossed paths with Rhys in person that I began to get a real sense of what made him so remarkable. As a young, nervous, foreign postgraduate student feeling his way into the world of American academic conferences, Rhys immediately welcomed me and took me under his wing. As Shane White recently pointed out, Rhys had an extraordinary way of talking to younger scholars that made them feel as though they were at the very center of the historical enterprise. He got excited about new ideas, and he helped make connections between fields, and even disciplines. With his infectious enthusiasm, he motivated and inspired people to think differently about their work and to take it seriously.

And he engaged with everyone. Rare was the conference session where Rhys would not rise at the end and ask an incisive question, make a suggestion, or even give a speech from the floor. Though he would often range widely, his comments inevitably touched upon each of the papers given, and invariably made the authors think differently about their work. He would be the first to congratulate the speakers and the last to leave the hall—deep in conversation, he was more often than not thrown out by security staff or anxious organizers keen to get delegates to the next session. He also closed down a few pubs. You were more likely to find Rhys in the middle of a beer-swilling pack of graduate students at the local watering hole than at the head of the table at a swanky postconference dinner. Rhys loved those evenings. He revelled in them. Many a breakfast was spent with Rhys recounting whom he had met the night before, what they were doing, and how exciting he found their work.

Indeed, Rhys was a true democrat. He believed the American Revolution was a profound event for ushering in the idea of equality. Though he knew the outcome was flawed and that true equality is still an elusive ideal, he lived and breathed the principle. He respected the work and ideas of men and women, young and old. He listened to their stories. He learned as much from the lifeguard at the beach as he did from his fellow professors. He felt as at home among his students as he did with the Harvard University trustees. It was a rare occasion when Rhys failed to animate his fellow dinner guests and break down any barriers of race, class, and gender that might have lent a stiffness to the proceedings. He eschewed empty formalities, abhorred pretention, and had no time for materialism (he once gleefully clambered under my battered old car to help me duct-tape it back together so it could pass the annual road-safety inspection). There were, in the end, few people Rhys could not charm. Rarely did he fail to bring out the best in those he met. And he embraced and learned from them all.

Part of his genius in both his personal and professional life was his tremendous ability to empathize (think for a moment of his critical yet tender appraisal of Landon Carter). He cared deeply about people, past and present. We bonded over loss. In 2000, my Mum and I travelled to Australia. Ostensibly there for an ANZASA conference in Sydney, we were also on holiday to escape grief. My father had died in 1996. My brother died three years later, in 1999, at the age of 33, after a long and exhausting battle with cancer. Rhys, not knowing these circumstances, insisted we come to Melbourne and stay with him and Colleen, and of course his two beloved cats. Over dinner, our story inevitably unfolded. When I came to my brother’s death, Rhys literally dropped his knife and fork, stood up, and with tears in his eyes came around the table to hug both my Mum and me.

It was then I found out that Rhys also lost his brother—his twin brother—Glynn, at an early age. Born on either side of midnight, Rhys’ parents never told him or his brother who was born first. Both grew up in Cape Town, as the architects of apartheid erected and applied new laws with an increasing ruthlessness. Both developed a keen sense of injustice and fought it on all fronts. Rhys chose the discipline of history to carry on the struggle. Glynn became a leader in the field of paleoanthropology and worked with Richard Leakey among the fossils of the East African plains. Rhys delighted in Glynn’s most important findings about the importance of foodsharing among early humans. He believed that sitting down to eat together, sharing food, was one of the hallmarks of humanity. After Glynn’s death at the age of 47, Rhys did all he could to continue to honour the memory of his brother and his work. On our last visit to Rhys’s beachside “Shamba” on the Mornington Peninsula outside Melbourne, we shared the house with a visiting anthropologist who was writing about Glynn and his work. Rhys delighted in relating his memories in hours of interviews and in sharing plenty of wonderful repasts with all his guests. Every shared meal became testimony to Glynn’s work and his memory.

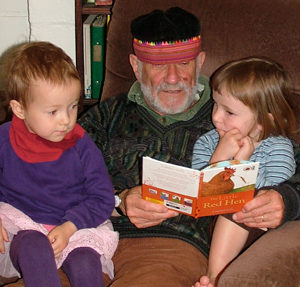

Rhys’s devotion to his brother was typical of his devotion to his family in general. As his sister Alison wrote recently, he was a devoted husband to the indomitable Colleen and father of two wonderfully smart and independent daughters, Megan and Lyned. His home was always filled, too, with children of colleagues, cousins, and nephews, all of whom Rhys would, with characteristic energy and enthusiasm, initiate into the world of picnics, beach visits, bush walks, and sailing. He was a proud grandfather to Lyn’s daughter, Amarana. He delighted especially in reading stories with her, and he had a huge folder of photos on his laptop that he proudly brought out whenever he visited. Ten days after Rhys died in early October, Lyn gave birth to another grandchild, Orrin—the first male in the direct Isaac line since 1937, when Rhys and Glynn were born.

Rhys’s “family” did not stop there, however. With the passion of a new immigrant, he built up an extended family that cut across countless different lines and layers of relationships. Lured to Australia shortly after finishing his degree at Oxford, he taught for many years at the University of Melbourne before joining a newly established history department at La Trobe in the city’s suburbs. Melbourne proved a fertile ground for new ideas—it was there that he famously collaborated with colleagues Inga Clendinnen, Greg Dening, and Donna Merwick, among many others.

He loved his new home. never looking back, he embraced everything Australia had to offer. A passionate advocate of history, he taught scores of students in the ethnographic method, and he left a trail of grateful students and colleagues in all manner of fields throughout the country and beyond. Certainly, as Shane White has noted, Rhys’s work gave a lustre and legitimacy to those of us who live in the antipodes and write about American history. Beyond that, he gave explicit support to the American Studies community in general—as a stalwart at the biannual ANZASA Conference (where he was one of the few who could be counted upon to begin the post dinner rounds of singing)—and as a warm colleague, mentor, and friend to so many of us.

When Rhys found out that my partner and I were interested in moving to Australia, he was delighted and did all he could to encourage us. And knowing the difficulties of settling in a new country, far from family, Rhys became family to us. He would send messages of encouragement to my South African partner in bastardised Afrikaans and happily reminisce with her about UCT and the wondrous mountains of the Cape Peninsula. When our daughter was born in 2007, Rhys wasthe first to visit her in the hospital, and he thereafter developed a special relationship with her, becoming a surrogate grandfather for her, as he did for so many other friends’ children. That we gave her a Welsh name—Carys—delighted him. And she found his snowy beard fascinating. For her, he is still affectionately “Rhys-ie.” Emailing her three days before he died to say thanks for a card she had made and sent him, Rhys signed himself “your bearded friend.”

Reading to his granddaughter Amarana (left) and Carys McDonnell (right). Photo courtesy of the author.

To the end, Rhys maintained these dual roles. On one hand, in those last months we traded manuscripts back and forth, Rhys characteristically expressing unqualified (though not uncritical) support for my new book. On the other, even in a weakened state he insisted on visiting us in Sydney to see our little boy born in June 2010, before we left on a sabbatical trip. As it turned out, he couldn’t make the trip up to Sydney, so we went to him in late August. My last memories of Rhys are of his steely resolve to heal the cancer within him, of talk about work he had just completed on the “french traveller,” of him sitting at the side of the bath singing songs with my daughter and later reading stories to her, of us all sharing one last meal together.

Rhys will be missed. He is irreplaceable. But while his work will give him a kind of immortality that few can dream of, I think he would be more than a little pleased to know that he has achieved a kind of immortality not just in our heads, but in our hearts.

Michael A. McDonnell,

University of Sydney