Trekking with Thad, by Michael L. Nicholls

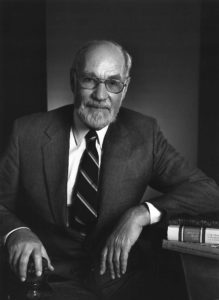

Photo Credit: ©1988 Yousuf Karsh

- Obituary for Thaddeus W. Tate, Jr.

- A Conversation with Thad Tate, by Fredrika J. Teute

- Travels with Thad, by Warren M. Billings

- Remembering Thad Tate, by Chandos Brown

- In Memoriam: Thad Tate, by Norman Fiering

- Trekking with Thad, by Michael L. Nicholls

- In Memoriam: Thad Tate, by Thad Weaver

Trekking with Thad

I met Thad in 1967 when I entered William and Mary’s new doctoral program in Early American History. He gave directed readings to us and I sat in on a history of early Virginia that he offered to undergraduates. Richard Maxwell Brown was my dissertation director, but Thad was the most important reader because it was a Virginia based study, his own geographical area of interest. His mentoring and professional encouragement continued for decades. We became good friends through other shared interests. During one summer in college, I had been a brakeman on the Rock Island Railroad working out of Des Moines, primarily on freights and locals with an occasional stint on the Rocket. This, of course, dovetailed with Thad’s love of all things railroad. I also taught in Utah, a wonderful location for backpacking and exploring the rugged beauty of the mountain west. Our home became a base for a series of backpacking trips in the mountain ranges surrounding our region.

In 1977 I hiked into the Blue Ridge for a short distance with Thad and Emory Evans and his sons after bringing them to a trailhead. Soon, Thad, Emory, Chris, and more frequently Philip Evans came to Utah for a series of hikes that spanned the next decade. Emory brought organization to our trips, and Thad plotted our paths on topographical maps. We trekked into the Wind River and Teton Mountains of Wyoming, the Needle Mountains of southwestern Colorado, and for Thad, the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho and the Ruby Mountains of Nevada. On the latter hike, he and I spent a night in Jarbidge between the Sawtooth and Ruby Mountain legs of the trip. It is an old and remote Nevada mining town and it is where we both picked up giardia. We should have anticipated it. As we left town we saw a cow straddling a fence next to a sign identifying the poorly fenced spring as the town’s water supply. Upon diagnosis, my doctor prescribed a medicine and warned me not to drink any alcohol; Thad’s doctor gave him the same prescription but, Thad said, had not mentioned abstaining, or perhaps he hadn’t heard those instructions. We decided it reflected the cultural differences between Utah and Virginia.

Joining this corp for at least one of these trips were colleagues of mine and a former student, Jim Boatwright, who was playing for Maccabi Tel Aviv. They had beat the Russians and gone on to win the European Basketball league. Thad’s godson, Thad Crowe, and Emory’s colleague, Ira Berlin also joined the crew, both on different trips into the Wind Rivers. In 1979 Larry Gerlach, who had once taken leave from the University of Utah to serve a year as book review editor at the Quarterly, and his wife Gail hiked into the Wind River range with us for a few miles and lent us their VW bus for the return trip. On that hike we were all challenged to keep up with Boatwright, whose height, at 6′ 8 or 9, produced a stride that should have been hobbled. On one part of the trip we got strung out along the trail, and Thad, who happened to be in the rear, was soon left behind. He did not show up when we took a break, so I hoofed it back looking for him. I soon found him, a bit battered and bruised from a fall, and concerned that the tumble may have injured his recently repaired detached retina. In spite of the physical dangers of fording rivers and streams, balancing on slippery makeshift log bridges, and scrambling up and down steep and slippery slopes, it was the only time I saw fear in his face. I also glimpsed anger for having been left behind.

Before our fifty mile hike into the Needle Mountains and the Weminuche Wilderness we visited Mesa Verde and then climbed onto the Durango and Silverton narrow gauge steam powered train to reach the trailhead. Thad was in heaven; history, trains and the wilderness all rolled into one. Many of the trips required driving to distant traiheads on roads that paralleled or crossed seldom used or abandoned railroad tracks. Invariably, Thad not only identified the line, but gave some idea of its connections and history. As others have noted, as a kid he absorbed railroad timetables like other boys soaked up baseball statistics from their collection of cards.

Our son Thad, his namesake born in 1979, and our daughter Sarah were soon calling him “Uncle Thad.” Our Thad hiked with Emory and Ira into the Wind River and Sawtooth ranges, but by that time, Thad’s increasingly frail knees and hips, all of which were to be replaced, had ended his backpacking. Thad continued to come west, however, for trips with our family to national monuments and parks, and archeological and historical sites around Utah. In 2009 Thad flew to Salt Lake for the Institute Conference, which required the crucial assistance of Beverly and Doug Smith. From there my wife Linda and I took Thad to Great Basin National Park, which contains Nevada’s highest peak, and to Ely, where a steam train and railroad museum remained on his not-yet-visited list. We had a great ride and then moved on to Elko for a final glimpse of the Ruby Mountains we had hiked nearly thirty years before with Larry Gerlach and his son TJ. That evening as we got ready to go to a Basque restaurant (even on hiking trips he and Emory sought out the most interesting places to eat) Linda and I heard loud expletives, likely learned from his service in the Navy, coming from the adjoining room. I checked and Thad came to the door as if nothing had happened, but confessed over dinner that he couldn’t get the shower to work as he wanted. As we drove home the next day we shared memories of our trip into the Rubys with Larry and TJ, of Jarbidge and giardia and of our other treks into the magnificent mountains of the West. He was a man to match them.

Michael L. Nicholls

Prof. of History, Emeritus

Utah State University