Revolutionary Narratives, Part 2

Reconsidering Commemorations at the U.S. 250th

This past summer, over twenty OI Associates from the U.S. and Canada rose out of their beach chairs once a week to tune into an OI Coffeehouse on the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States. Organized by Maria DiBenigno, Hilary Miller, and Amy Speckart, three members of the Revolutionary Narratives working group, the Coffeehouse asked participants to reflect on past commemorations in the U.S. and prognosticate on what 2026 will look like at historic sites, museums, libraries, archives, schools, and universities.

Uncommon Sense has been sharing some of the broad thinking that the Coffeehouse inspired in a three-part blog series. In the second part of this series, we explore how symbols of the American Revolution were used to demand rights and create a problematic sense of national identity in the United States.

Part 2: Symbolism and National Identity After the American Revolution

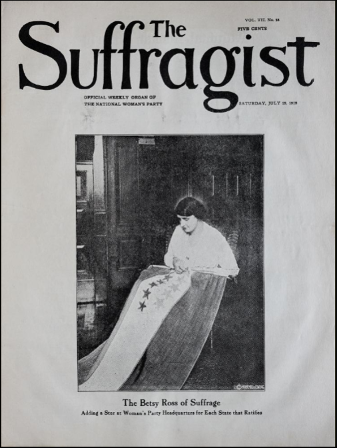

In July 1919, the National Woman’s Party (NWP) journal featured a posed photograph on its cover: a seated woman at work, her eyes cast down to the sewing in her lap. She was carefully stitching a five-pointed star to the surface of a flag. Text below her reads: “The Betsy Ross of Suffrage.” Some viewers were surprised by this image, as the NWP was often described as the more “militant” wing of the suffrage movement in the United States. Claiming Betsy Ross, a figure long associated with patriotic domesticity, might have come as a surprise. Others decried suffragists’ reclamation of Ross as an act of “desecration” of the flag.[1] But suffragists asserted their right to Ross as they stitched stars on the Ratification Flag, marking each state’s ratification of an amendment granting women voting rights. This, they asserted, was a continuation of the nation’s founding story. Their Betsy Ross stitched an expanded union.

These stitches were a coded performance: suffragists presented themselves as inheritors of Betsy Ross’s multivalent legacy, rendering themselves legible as part of an existing story. But they also reached back into the past and reshaped the resonance of the Ross myth, illuminating the exclusivity of the original flag. The myth of Betsy Ross’s sewing of the first American flag bears only slight resemblance to the actual life and labor of Elizabeth Griscom Ross; she was an upholsterer and savvy businesswoman who was later repackaged as a nostalgic, domestic heroine. But the NWP’s move to expand the vision of what Ross might represent and, by extension, who might be included in the national mythology was a creative act of commemoration. I’m struck by one image of Alice Paul and other members of the NWP gathered over the Ratification Flag.

This busy photograph positions the work of making the nation, of re-remembering who we are as a communal, material process. This was a limited remembering; we can read many of the biases and tensions of the movement in the ways some suffragists claimed their inheritance of this white, nostalgic, feminine figure. But this image kept returning to me throughout our coffeehouse sessions, reminding me that we choose how to assemble ourselves from the remains of what has been. Moments of remembrance have long given us an opportunity to re-examine the figures we use to make sense of ourselves, to ask if we see ourselves in the past and if we see the futures we hope to craft.

[1] Description of the DAR’s consternation over the “flag incident” is documented in Anne Fitzhugh Miller’s NAWSA Suffrage Scrapbooks, 1897-1911, Library of Congress. See Scrapbook 9 (1910-1911).

—Mariah Kupfner is Assistant Professor of American Studies & Public Heritage at Penn State Harrisburg

I joined this coffee house from a desire to think more deeply about reinterpreting the American Revolution in our complicated cultural-political moment. However, as our conversations raised questions about whose 250th the upcoming anniversary will be—or could be—someone referenced the old adage of America as a melting pot. Did you know that The Melting Pot was originally a play, I asked? Written by a Jew from London in about 1910? They did not. And thus, some prior research of mine became the focus of a weekly discussion, as well as a renewed subject of my own contemplation.

The Melting Pot, a play by British Jewish author Israel Zangwill, premiered in Washington, D.C. in 1908, and was published in book form by 1909. Zangwill’s play gave name to a specific aspiration for American exceptionalism at the height of European immigration: that the U. S. as a powerful crucible of democracy could absorb and homogenize its multitudes of newcomers, merging their separate nationalities, races, cultures, religions into something that much stronger—much like a metal alloy that is superior to its individual elements.

The plot echoes earlier tales of star-crossed lovers, as David and Vera—both immigrants, one Jewish, one Orthodox Christian—meet through a New York Settlement House. David is a musician striving to compose a symphony that embodies his glorious vision for America’s immigrant millions. As plot twists tied to old-world trauma drive the lovers apart, David finishes the symphony in anguish, and the lovers reunite after its triumphant performance. Against a flaming sunset overlooking New York Harbor, David once again proclaims his vision: “There she lies, the great Melting Pot—the harbor where a thousand mammoth feeders come from the ends of the world to pour in their human freight…. how the great Alchemist melts and fuses them with his purging flame!”

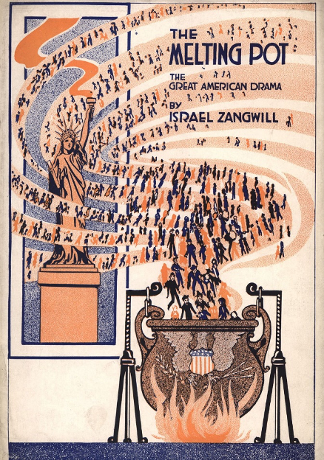

The cover of a 1916 brochure for a traveling version of The Melting Pot is striking for the way that it codifies this image. Streams of human bodies float on swirls of air that twist around the Statue of Liberty. The bodies fly closer, now on their way to the mouth of a giant cauldron sitting atop an active flame. The closest bodies drop into the cauldron a few at a time and disappear. Where have they gone? On the back, the play’s summary touts “Zangwill’s prophetic vision of America’s future as the crucible in which the remnants of old nations shall be melted to form a New Race.”

New Race indeed, or “perhaps the coming superman,” to quote David in the play. Race in The Melting Pot is not what we mean by race today. Theodore Roosevelt lauded the play, and Henry Ford established a Melting Pot ceremony for immigrant graduates of his English School. Objections to the vision as coerced assimilation appeared early and often, at the same time it achieved broad acceptance in the popular mind. Some hundred years later, America as a melting pot is a well-worn and possibly failed cliché—today we are just as likely to celebrate our ethnic and cultural differences as our national commonalities. But the appeal of American exceptionalism runs deep, as do the messy entanglements of race in American society. Did The Melting Pot’s hypothesis help or hurt us in the end? How has it shaped our present self-conceptions? With this example, I am reminded that our foundational “revolutionary narratives” intrinsically date from all along the trajectory of U.S. history.

—Susan Garfinkel is a research librarian at the Library of Congress and affiliated scholar in American Studies, University of Maryland, College Park

The Revolutionary Narratives Working Group, made up of public history practitioners and academic scholars, is dedicated to fostering discussions about how to achieve a diverse, inclusive, and equitable U.S. Semiquincentennial. You can say hello to us in person at OAH 2024 in New Orleans at our session titled, “To 2026 or not to 2026? Commemoration, Reflection, and the Role of Historians in the U.S. Semiquincentennial,” or email us at RevolutionaryNarratives@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply