“A Good Receipt for the Womb:” Lady Augusta Murray’s Book of Cures

By Ann M. Little, Colorado State University

Professor Little was awarded an Omohundro Institute—– Georgian Papers Programme fellowship in 2016 and conducted research in the archives at Windsor Castle in summer 2017.

Applications for the fall 2020 round of Georgian Papers Programme fellowships will be posted on the OI website later in August.

Amidst our twenty-first century Coronavirus pandemic, we find ourselves fighting disease with very old-fashioned tools and strategies that take us back before the era of antiviral medications, and vaccines. When faced with a highly contagious virus with no reliable therapy and national governments that aren’t providing steady and reliable advice about public health, modern Britons and U.S. Americans find ourselves back in the premodern era with premodern tools and strategies for ensuring the health of our families and communities. Soap, water, and physical barriers like masks and distancing are our most reliable preventives.

Over the past four months on lockdown with my small family, I’ve looked back with fond nostalgia to my Georgian Papers Programme fellowship in the summer of 2017, back when international travel and archival research were the typical events in my summers, not to mention drinks at the pub with fellow researchers and evensong in St. George’s Chapel. In my research on women in the Age of Revolution, I found myself in the mumsy lair of the Royal Archives reading room in Windsor Castle sifting for the proverbial needles in haystacks that would offer details about the everyday lives of women in the court of King George III and Queen Charlotte. Among the sharpest and most fascinating needles presented to me was Lady Augusta Murray’s Book of Cures. Entirely digitized for your pandemic perusing pleasure, it spoke to me as a scholar and a woman, especially now that we’re relying once again on premodern technologies to prevent and treat this novel disease.

Lady Augusta Murray (1768-1830) was the clandestine wife of Prince Augustus Frederick (1773-1843), the sixth son of George III and Charlotte. She was the daughter of John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore and the last royal governor of Virginia. They were legally married in Rome in 1793 and again in London in 1794 without the consent or knowledge of the King and before the Prince was of the age of majority. Because this contravened the Royal Marriages Act of 1772, the marriage was annulled the following year after the birth of their son Augustus. Lady Augusta and little Augustus lived separately from the Prince when he was sent to Italy by his family; he lived with another woman for a time, and presumably Lady Augusta was free to pursue other amours. The family reunited in 1799 and 1800 but dissolved before the birth of their daughter Augusta in 1801. Lady Augusta was then again left alone to raise her children. Her Book of Cures, dated to the birth of her first child and kept from the years 1794-1812, shows that she was intimately involved in their nutrition and health care.[1]

Like so many women’s books of “receipts” in the early modern era, Lady Augusta’s book included both medicinal and culinary preparations and diet advice, as common herbs, extracts, and kitchen ingredients were used in all of these.[2] The medicinal preparations were focused on the body’s production of waste material to restore health, so purgatives to induce sweating, emetics, diuretics, and laxatives were commonly prescribed. They may not have worked to cure coughs or the common cold—or deadlier maladies like measles—but they produced powerful effects on the patient as well as something for healers and physicians to examine. (And if used moderately, they were less dangerous than bloodletting, another practice designed to take something hidden inside the body outside of it for inspection.)

While the guard changed several times a day below our window from the castle keep on the Upper Ward, I reflected on the private hopes and fears of a royal mistress. Lady Augusta’s Book of Cures suggests that she had a very modern-seeming maternal concern for the day-to-day health and well-being of her children. The connections to Lady Augusta’s American contemporaries seemed very clear: Linda Kerber’s groundbreaking Women of the Republic: Intellect &Ideology in Revolutionary America examined the emergence of what she called “Republican Motherhood,” which was both a literal and a metaphorical concept. Motherhood—of the nation, and of specific children, became in the early U.S. republic the only possible public role for the vast majority of free American women, and public mothering became the pretext for several progressive nineteenth-century reform movements like temperance, Sabbatarianism, abolition, and feminism. Susan Klepp argues in Revolutionary Conceptions: Women, Fertility, and Family Limitation in America, 1760-1820, that ironically (or not), this new vision of motherhood relied on a measurable fertility decline: as middle-class women absorbed enlightenment and revolutionary ideology and intentionally limited the size of their families, Klepp argues, they not only had time for the civic involvement described by Kerber, they also had more time and attention to pay to each child’s education and health.[3] The Book of Cures suggests that Lady Augusta was more like these American women who were having smaller families at the turn of the nineteenth century than she was like Georgian-era mothers of previous generations, as it offers powerful evidence that she was keenly interested in limiting her fertility as well as in the health and survival of the children she had.

By her biography and that of her two children, she succeeded on both accounts: she gave birth to two children, and both lived to adulthood (indeed, even to middle- and old age): Augustus (1794-1848) and Augusta (1801-66). The Book of Cures testifies to her maternal devotion in large and small ways, cluttered as it is with affectionate asides to many of the cures for “my boy,” or “my loved girl,” such as “the 19th 7br (September) 1803 – Purgings what cured my boy of his dystentery.” (Curious? It was a linament of mutton fat and at night one pill containing two grains of calomel—mercurous chloride—and one grain of “Extract of Opium,” along with doses of castor oil.) Just a few pages later, among some “strengthening receipts,” she offers “a tonic for my Boy after his stomach is deranged by a Cough,” dated 1805 when Augustus was eleven.[4] Even more frequently than she references “my boy,” she calls him “my Treasure,” as in “Dr. Rowley’s prescription to stop my Treasure’s purging 7br 3rd 1796,” “Dr. Crowley’s receipt for my Treasure April 98 for a cold & feverish Cough,” and various preparations for “Coughs/for my Treasure.”[5]

Young Augusta, born around the time her parents’ relationship dissolved permanently, came in for similar affectionate references in the Book of Cures—remedies for everyday coughs and colds as in the case of her older brother: a remedy dated 1805 “for my little Girl’s feverish cold,” and an 1811 recipe for a nervous cough from “Dr. Grey for my loved Girl.” While her brother seems to have suffered more from upper respiratory conditions, with several cough and cold remedies to his name, Augusta endured a more serious childhood disease when she was only three, as her mother recorded “Dr. Holland’s treatment of my Girl in the measles” in late 1804. She was also prescribed a “treatment for my Girl recommended before sea bathing” the following year, in 1805. This latter prescription was a combination of magnesia (a laxative), “Ethiops mineral” (a worming agent), and “Sal polychrest” (a double salt of potassium sulphate and potassium nitrate), “to be taken every other day in milk & Water sweetened”—pretty strong stuff for a girl not yet four to take before a swim. Remedies like this one, purgatives laced with strong chemicals, sit side-by-each with much tastier “kitchen physick,” like “C. Murray’s Strong Ginger Calmer for the stomach,” consisting of six pounds of sugar boiled with 12 ounces of powdered ginger and then cooled on a plate—and presumably broken up and consumed like hard candy. An even stranger culinary-style medicinal preparation immediately follows the sea-bathing prescription for young Augusta. “The way to take Castor Oil” involves making a kind of sweet mayonnaise with an egg yolk, castor oil, and brown sugar which was then thinned with “cinnamon water.”[6]

Lady Augusta’s small family was of desperate concern to her not only because of the ties of maternal affection, but also most likely a financial matter: the royal family would presumably have been much less likely to support her if one or both of the children died. With two children in the picture, and only after taking the royal family to court because of the debts Prince Augustus had left her with, she was granted an annual income of £4,000, plus a further allowance for the children.[7] Because the marriage had been annulled immediately after the birth of her son, her children with Prince Augustus would never be considered legitimate heirs. The survival of Lady Augusta’s children was therefore not a matter of succession to the throne, but they were key to her claim on an income from the royal family. But Lady Augusta not only took steps to care for the children she had, she also recorded remedies to help her avoid having children she didn’t want. The Book of Cures contains considerable evidence—much of it written in French, rather than English—of remedies for stopped menses: in other words, emmenagogic preparations that might have served as abortifacients. If she pursued other love affairs while hoping for a reunion with the Prince through the 1790s, she was armed with remedies to help her void any pregnancies that might have ensued.

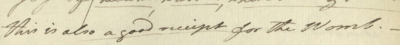

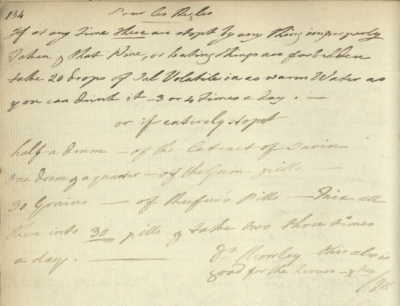

As Klepp and others have argued, menstrual regularity was a proxy for women’s health and well-being; stopped menses, whatever the cause, were a signal that a woman’s health might be impaired. The fact that stopped menses could also be a symptom of pregnancy was an ambiguity that many women and pharmacists could exploit in case pregnancy wasn’t desirable, and folk remedies as well as patent medicines circulated widely in both North America and Europe for women in need of menstrual regulation or restoration.[8] Like so many women in the Age of Revolutions, Lady Augusta seems to have been a loving and devoted mother, but her vision for childbearing was finite. It was perhaps the most exciting discovery of my summer in the Royal Archives when I read Lady Augusta’s prescription “Pour les Regles” (menses, or “monthlies,” might be a better translation): “If at any Time these are stopt by any thing improperly Taken & that Wine, or heating things are forbidden take 20 drops of Sal Volatile (ammonium carbonate, or smelling salts) in as warm Water as you can drink it—3 or 4 times a day.” “Or if entirely stopt,” the advice continues, “half a dram—of the Extract of Savin one dram & a quarter—of the Gum pills 30 grains—of Rufus’s Pills—Mix all these into 30 pills & take two three times a day.” Savin was a known abortifacient, and Rufus’s Pills were evidently a commercial purgative with aloe, saffron, and myrrh. This page is dated “Xber (October) 98,” a year before her reunion with the Prince.[9]

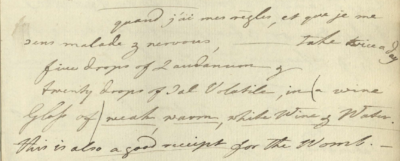

On the very next page, Lady Augusta recorded another regime “Pour les règles, douleur d’obstructions &c,” (for the menses, painful obstructions, etc.), this one dated very specifically to June 20th, 1799. Women doubtlessly had an interest in recording these remedies whether or not they had a specific need for them at the moment—the very act of recording abortifacient remedies or other recipes to restore menstruation was an effort to preserve the information for future as well as immediate future use, by oneself, or perhaps friends or family members. But the timing of these recorded preparations is interesting, as it too was recorded before she resumed family life with the Prince that autumn. The 1799 recipe involves bathing as well as a medicinal preparation taken internally: “If a warm Bath can readily be procured So use it Every 2d Evening just before the change takes place, & one of the draughts written under at bed time.” What follows is a recipe that included a known abortifacient—pennyroyal—and a narcotic (10 drops of laudanum), along with more neutral ingredients like “Tincture of Castor,” “mucilage of gum Arabic,” and “Syrup of saffron.” Taken every other night, “this is an Excellent receipt for pains at a certain time.” This last comment suggests that it might also have been recommended for common menstrual cramps, but the inclusion of “Simple pennyroyal water” in the preparation suggests that restoring the menses, not just relieving their symptoms, was the main goal.[10]

Several other preparations in the Book of Cures are for gynecological complaints and discomforts. “Quand j’ai mes règles, et je me sens malade & nervous, –take twice a day” (when I have my period, and I feel sick and nervous), she recommended a mixture of laudanum, sal volatile, water, and wine. “This is also a good receipt for the Womb,” she noted. Lady Augusta also recorded other preparations for the health of the womb, including three for “spasms” in the womb that relied unpleasantly on harsh laxatives (Epsom salts taken orally) followed by enemas of laudanum and oil. Orally-ingested laxatives in high doses combined with culinary herbs like rose and mint were common in these preparations, as were opiates, which offered pain relief as they purportedly contributed to “opening” the womb or relieving cramps or contractions caused by either spontaneous or induced abortions.[11]

Lady Augusta Murray—later De Ameland—practiced seduction and motherhood at the most modern and knowledgeable level achieved by women in the Age of Revolutions. A minor satellite of the late eighteenth-century Georgian court, her Book of Cures is a suggestive document about the lives of elite British women and the possibility that some might have shared the goal of a small, successful families with other middle-class and elite women in the U.S. and France. Although Britain didn’t experience a fertility decline until the mid-nineteenth century, Lady Augusta’s Book of Cures suggests that at least some British women were determined to exert control over their fertility fifty years earlier.[12]

[1] For the Book of Cures and biographical facts about Lady Augusta Murray, see https://gpp.rct.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=MURRAY&pos=2, accessed July 16, 2020; Flora Fraser, Princesses: The Six Daughters of George III (New York: Knopf, 2005), 152-54; 185-86; James Corbett David, Dunmore’s New World: The Extraordinary Life of a Royal Governor in Revolutionary America (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 1-2, 172-74, 179-83.

[2] See Londa Schiebinger’s discussion of “medical cookery,” or “kitchen physick,” in The Mind Has No Sex? Women in the Origins of Modern Science (Harvard University Press, 1989), 112-116; Anita Guerrini, “The Ghastly Kitchen,” History of Science 54:1 (2016), 71-97. See also “The Recipes Project: Food, Magic, Science, and Medicine,” a blog edited by an international group of junior scholars on the intertwined nature of these things in the early modern era, https://recipes.hypotheses.org/ (accessed July 19, 2020).

[3] Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect &Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980); Susan Klepp, Revolutionary Conceptions: Women, Fertility, and Family Limitation in America, 1760-1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

[4] Lady Augusta Murray’s Book of Cures, Georgian Papers Online (http://gpp.rct.uk., January 2020), RA GEO/ADD/51/5 (hereafter Book of Cures), 163, 166; see also 63, 79.

[5] Book of Cures, 68, 92, 124-25; see also 139, 144, 164. Charmingly, or tragically, David quotes Prince Augustus calling Lady Augusta “my treasure” in affectionate correspondence commemorating in 1796 the third anniversary of little Augustus’s conception: “To this day my treasure do we owe the origin of our dear little boy. . . . This day three years ago was the first full Pleasure I enjoyed of my Wife,” 179. The Prince had been separated from his family for two years when he wrote this.

[6] Book of Cures, 83, 123, 170, 176-77.

[7] David, 179-83.

[8] Klepp, “Lost, Hidden, Obstructed, and Repressed: Contraceptive and Abortive Technology in the Early Delaware Valley,” in Early American Techology: Making & Doing Things from the Colonial Era to 1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 68-113; Klepp, Revolutionary Conceptions, 179-214.

[9] Book of Cures, 134; “Rufus’s Pills,” The Cullen Project: The Consultation Papers of Dr. William Cullen (1710-1790) at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh,” http://cullenproject.ac.uk/items/i497/, accessed July 17, 2020. For a discussion of the English and North American herbs used by women to restore their menses or induce abortions, see Klepp, Revolutionary Conceptions, 189-194.

[10] Book of Cures, 135.

[11] Book of Cures, 137, 165-66, 169, 186.

[12] The British fertility decline happened nearly a century after the U.S. and France, from 1850-1930. See Michael S. Teitelbaum, The British Fertility Decline: Demographic Transition in the Crucible of the Industrial Revolution (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984); and Jane Humphries, (2006),`Because they are too menny…` children, mothers, and fertility decline: The evidence from working-class autobiographies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, No _064, Oxford Economic and Social History Working Papers, University of Oxford, Department of Economics, https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oxf:esohwp:_064 (accessed July 20, 2020).

The image of Lady Augusta Murray, painted by Richard Cosway, is used courtesy of the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art at Colorado State University. You can read a full description of the image here.