Edward Francis Countryman, formerly University Distinguished Professor of American History at Southern Methodist University, passed away in Dallas, Texas on March 24, 2025.

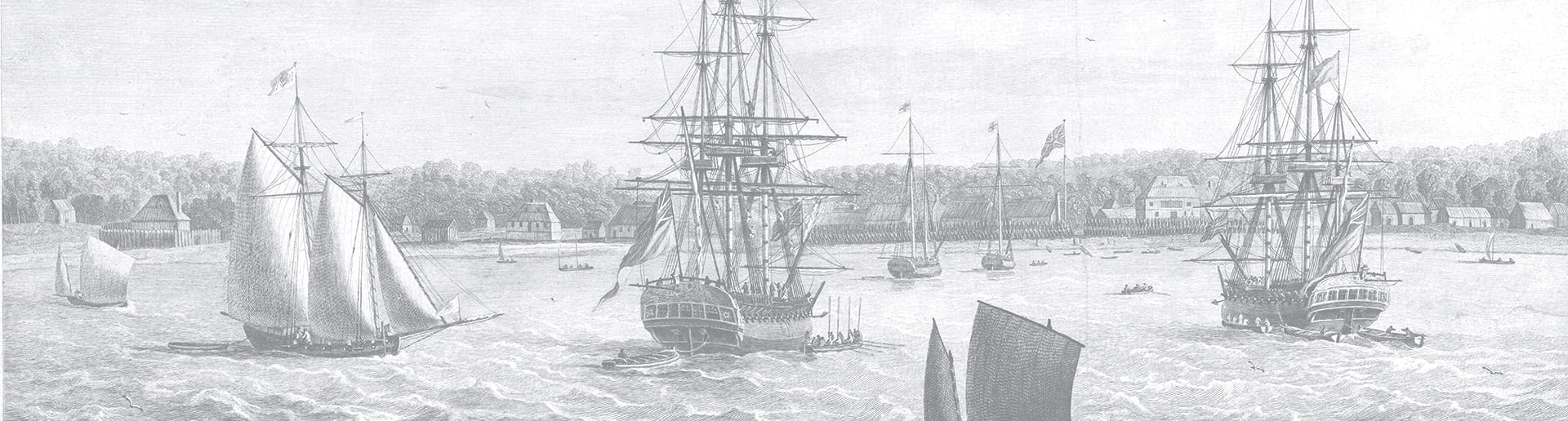

Ed was born in Glens Falls, New York, attended high school in Troy and earned his BA at Manhattan College. In graduate school at Cornell University he studied with Clinton Rossiter, James Morton Smith, Joel Silbey, and Hannah Arendt, among others. The dissertation he completed in 1971, he later wrote, was a “purely institutional study” of political parties in the New York legislature after independence. Already, however, and following a pattern that would persist throughout his long and fruitful career, he was reading broadly, influenced by ascendant behavioral political science and increasingly by European Marxist historians who had focused on rural and urban crowds, both of which had been so important in revolutionary New York. In a series of articles he began to focus on mobilization, politicization, transformation, and legitimation. This work culminated in A People in Revolution: The American Revolution and Political Society in New York, 1760-1790, a study that won universal praise in the sometimes contentious field of American Revolution studies. The book shared the Bancroft Prize in 1981.

Ed was born in Glens Falls, New York, attended high school in Troy and earned his BA at Manhattan College. In graduate school at Cornell University he studied with Clinton Rossiter, James Morton Smith, Joel Silbey, and Hannah Arendt, among others. The dissertation he completed in 1971, he later wrote, was a “purely institutional study” of political parties in the New York legislature after independence. Already, however, and following a pattern that would persist throughout his long and fruitful career, he was reading broadly, influenced by ascendant behavioral political science and increasingly by European Marxist historians who had focused on rural and urban crowds, both of which had been so important in revolutionary New York. In a series of articles he began to focus on mobilization, politicization, transformation, and legitimation. This work culminated in A People in Revolution: The American Revolution and Political Society in New York, 1760-1790, a study that won universal praise in the sometimes contentious field of American Revolution studies. The book shared the Bancroft Prize in 1981.

Teaching first at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand and then at University of Warwick in England, where he was an integral member of the School of Comparative American Studies, gave Countryman an outsider’s insider perspective on the American Revolution and the difference it made in U.S. history, and perhaps also on the dangers of overspecialization and “schools.” He was the only historian with essays in both of Alfred F. Young’s collections of new “neo-progressive” studies of the Revolution (1976, 1993). He carried on Young’s exemplary mentorship of younger scholars in the field after he emerged as a leading synthesizer with The American Revolution, published by Hill and Wang in 1985 (and in a revised edition in 2005). By that time, Ed had developed a punchy, straightforward style that made new scholarly concepts strikingly accessible. For decades a classroom standard, The American Revolution was deeply appreciated by historian peers, as Joyce Appleby put it at the time, for “integrat[ing] the new research on social groups with the work that has been done on political and ideological issues.” In Countryman’s American Revolution, as Gregory H. Nobles wrote in a 2011 review of the historiography, powerful men determined the course of the Revolution to their own ends, but ordinary people “still embraced its original spirit.”

He followed this work with an even more ambitious synthesis of the late-colonial period through Reconstruction. Americans: A Collision of Histories, was published in 1997 to wide acclaim. It was recognized as a bold and generous argument about how, as he put it in an op-ed in 1997, “the American identity we share grows precisely from our sometimes glorious sometimes bitter intersections with one another.” The nation and its controversial identities had all emerged from a common, and violent, history: understanding race and racism and the rest of U.S. history had to be seen as an entwined, ongoing project. Countryman’s 1996 William and Mary Quarterly forum article from this period, “Indians, the Colonial Order, and the Social Significance of the American Revolution” is now often cited for its argument that the best case for revolutionary dimensions of the Revolution, both in terms of causes and consequences, may lay in what happened between settlers and indigenous people.

After visiting professorships at Cambridge and Yale, Ed moved on in 1991 to a chaired professorship at Southern Methodist University. Much as at Warwick, where he had enjoyed the intellectual ferment around colleagues like E.P. Thompson, he profited from the influence of David Weber and other historians of the U.S. West who worked in and came through Dallas. He was especially proud of the collaboration that led to the field-defining collection on borderlands, Contested Spaces of Early America (co-edited with Juliana Barr, 2014), and of Shane (1999), his entry in the prestigious British Film Institute monograph series, co-authored with Evonne Von Heussen-Countryman. Enjoy the Same Liberty: Black Americans and the Revolutionary Era (2011) provided an up-to-date and classroom-friendly account of African American history, arguing persuasively that what Black people did in the period made the era truly revolutionary. Before “Vast Early America” emerged as name for a trend, in other words, Ed was going “vast,” showing us how it could be done, challenging himself to do more and better. During the 2000s and 2010s he put much work into mastering Native American history and consulting work for First Nations in his native New York. At the time of a debilitating accident in 2022, he was finishing his most ambitious synthesis of early American history, also under contract with Hill & Wang, entitled Troubles in a New World: Colonizing America, A Revolution, and a Fragile Republic. It is an unflinching, eloquent work of deep and broad vision that brings together the achievements of early Americanists in Ed’s lifetime with his distinctive insistence that, despite all the fragmentation in our knowledge and in our politics, these things do “hang together,” as he liked to say, modestly quoting another historian. In Ed’s hands, early America was vast but also deep, so deep that merely debunking or celebrating seemed beside the point. Some of his students hope to see this work through to publication.

Ed was an extremely dedicated teacher and mentor who spoke of his students with the greatest respect. He took special pleasure in crediting them in his own work, much of which he tried out in survey courses and seminars, teaching a range of popular courses and helping to build a robust graduate program. He liked to be challenged and always tried to meet people where they were. With friends, he had a wickedly sarcastic sense of humor, sometimes self-deprecating, sometimes needling, always caring. He loved music, art museums, literature with epic ambitions, film, long hikes, and marathon runs well into his seventies. He was a humble soul, forever a New Yorker, but nothing less than a citizen of the world. Ed is survived by his wife, sister, children, grandchildren, daughter-in-law and son-in-law, as well as many caring friends, colleagues, and former students who were touched by his wisdom and generosity.

—David Waldstreicher, CUNY Graduate Center