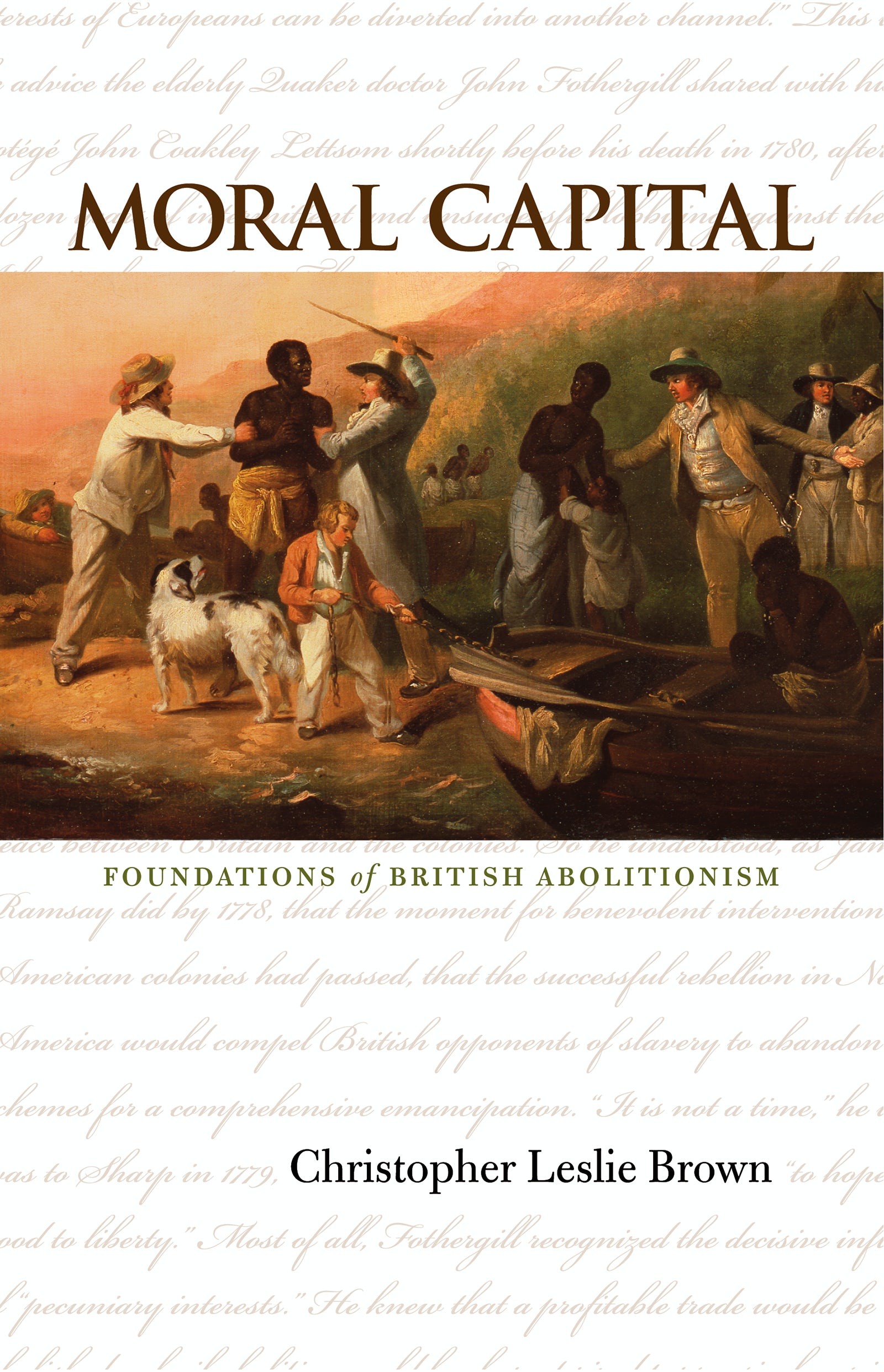

Description

Revisiting the origins of the British antislavery movement of the late eighteenth century, Christopher Leslie Brown challenges prevailing scholarly arguments that locate the roots of abolitionism in economic determinism or bourgeois humanitarianism. Brown instead connects the shift from sentiment to action to changing views of empire and nation in Britain at the time, particularly the anxieties and dislocations spurred by the American Revolution.

The debate over the political rights of the North American colonies pushed slavery to the fore, Brown argues, giving antislavery organizing the moral legitimacy in Britain it had never had before. The first emancipation schemes were dependent on efforts to strengthen the role of the imperial state in an era of weakening overseas authority. By looking at the initial public contest over slavery, Brown connects disparate strands of the British Atlantic world and brings into focus shifting developments in British identity, attitudes toward Africa, definitions of imperial mission, the rise of Anglican evangelicalism, and Quaker activism.

Demonstrating how challenges to the slave system could serve as a mark of virtue rather than evidence of eccentricity, Brown shows that the abolitionist movement derived its power from a profound yearning for moral worth in the aftermath of defeat and American independence. Thus abolitionism proved to be a cause for the abolitionists themselves as much as for enslaved Africans.

About The Author

Christopher Leslie Brown is associate professor of history at Rutgers University and coeditor of Arming Slaves: From Classical Times to the Modern Age.

Awards

James A. Rawley Prize, American Historical Association (2006)

The Morris D. Forkosch Prize, American Historical Association (2006)

Choice Outstanding Academic Title (2006)

Frederick Douglass Book Prize, Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition (2007)

Reviews

Brown’s Moral Capital is remarkable in . . . managing to say something genuinely new about a subject that has been discussed and written about for two centuries; and that . . . is no small achievement.–Times Literary Supplement

A crucial intervention in our understanding of the international pressures that led to . . . the term ‘British anti-slavery’. . . . . This meditation on the vastly complex social and iintellectual origins of British anti-slavery activism takes us back to basics, and asks radical questions that historians of the Atlantic diaspora will now need to ponder.”-American Historical Review

A provocative rereading of the origins of late eighteenth-century British antislavery. Beautifully written and elegantly paced. . . . [Brown’s] is an outstanding contribution to an enormous and critical historiography.–Journal of American History

An impressive array of primary sources. . . . Capturing the complexity of abolitionism’s development . . . A significant study that sheds new light.–The Journal of Religion

Elegant and persuasive. . . . Effectively reframe[s] our traditional portraits of antislavery as humanitarian reform more generally at the turn of the eighteenth century.–William and Mary Quarterly

A comprehensive and encyclopedic analysis of early British abolitionism that will be standard reading for all interested in the subject.–Journal of the Early Republic

This is a carefully crafted study that will be widely appreciated by historians of slavery, imperial history, the American Revolution and eighteenth-century British domestic politics.–Patterns of Prejudice

A major reassessment of a movement that has usually been studied from a much more limited perspective.–Itinerario

In what is likely to become a landmark study in the history of British abolitionism, Brown provides a nuanced and compelling interpretation of its roots. . . . This outstanding and timely study will have a broad impact. Essential.–Choice

Brown’s meticulous and lucid analysis of the self-regarding, self-interested, and self-validating impulse in British abolitionism presents a much more nuanced and compelling argument than we have seen before.–New West Indian Guide